essay by:

Emily L. Moore, Ed.D., Professor Emerita, Iowa State University, Higher Education

EL Moore © 2017

Editor’s Note: How the Smithsonian, National Park Service, and National Heritage Areas tell stories together

During the Alliance of National Heritage Areas (ANHA) Annual Meeting in February 2017, I had the honor of working with Brandi Roberts, Executive Director of Great Basin National Heritage Area (Nevada) Sara Capen, Executive Director of Niagara Falls National Heritage Area (New York) to organize a special ANHA tour of the new Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington, D.C. The tour was arranged in collaboration with Smithsonian Ambassador Mossi Tull and the museum's education division.

National Heritage Areas are cultural heritage partnerships with the National Park Service. The Smithsonian NMAAHC features exhibits that relate to many National Heritage Area stories, including the Mississippi Delta National Heritage Area and the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, which spans Lowcountry coastal communities shared by four states: North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

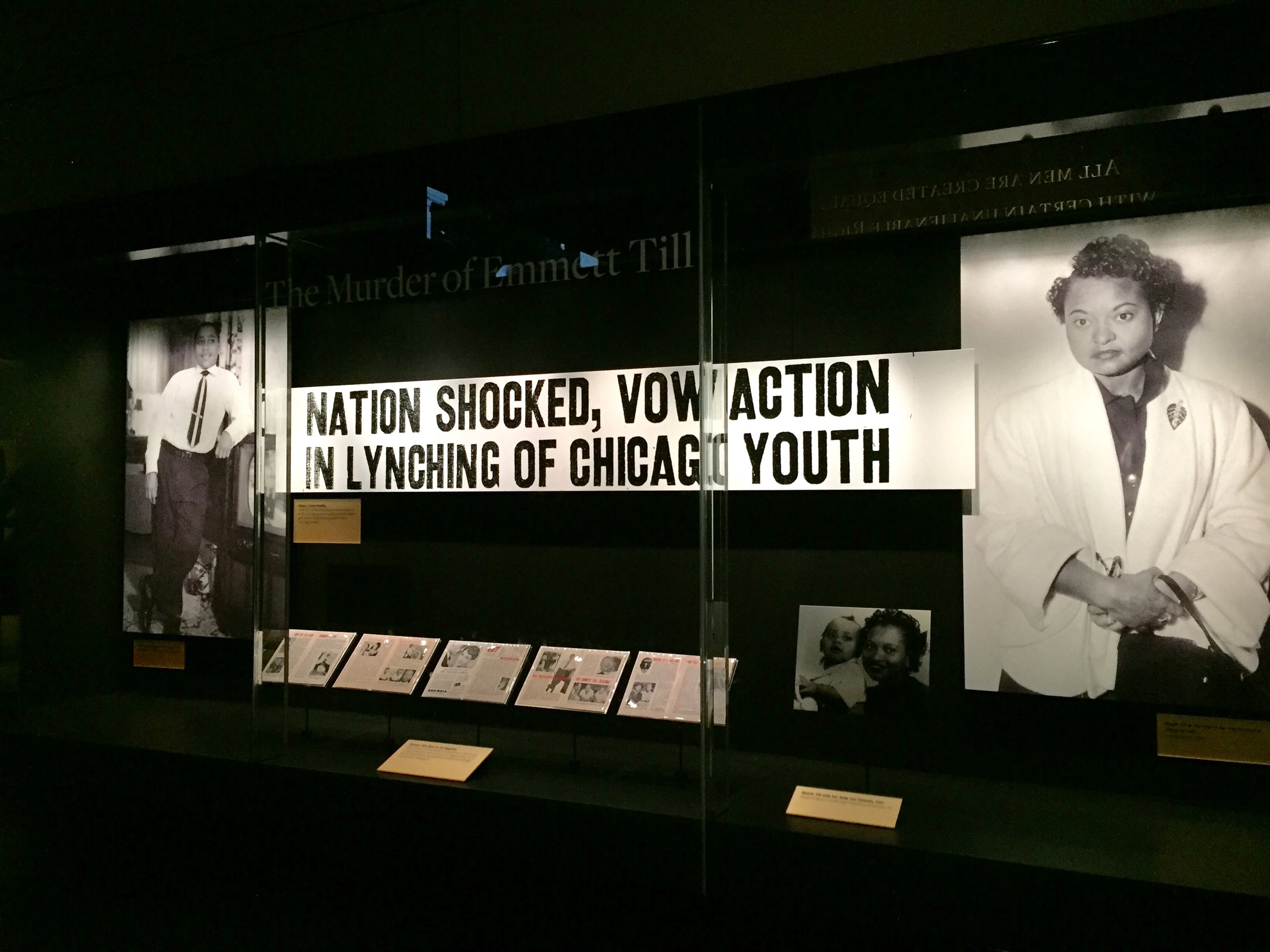

The following is a powerful reflective essay written by Dr. Emily Moore who experienced the tour with her husband, Dr. Herman Blake, Executive Director of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor. Dr. Moore’s personal account poignantly illustrates the enduring historical and cultural significance of a 1955 Mississippi Delta story that still resonates with 21st century America: the lynching of African American teenager Emmett Till, an international tragedy widely cited as the “spark that lit the fuse” of the modern Civil Rights Movement.

- Rolando Herts, Ph.D., The Delta Center for Culture and Learning and the Mississippi Delta National Heritage Area

On February 13th, 2017, during Black History Month, Herman Blake and I, with nearly one hundred other people from the Alliance of National Heritage Areas, experienced an opportunity of our lifetime – a guided tour by a docent of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), Washington D.C.

What made our visit so remarkable was: (1) at the time, there were no tickets available to visit the museum until April 2017; (2) the reality of Black History Month weighed heavily on us; and (3) our two-hour tour was provided before the museum opened to the public for the day. Thus, our group was alone to wander and tour the four level building; question and read; hear the music and see the artifacts; listen to the voices of the past with explanations from the docent; and remember the events that made us smile, hurt and struggle.

The power of the museum won’t let you be a visitor. You are a part of the reality of the exhibit. You cannot look away. You cannot say “I am not involved.” You are absolutely in the moment. And, then sometimes, you cry.

As written in their literature, this is “the only national museum devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, history, and culture . . . established by an Act of Congress in 2003 . . . and opened on September 24, 2016 . . . it has 36,000 artifacts and nearly 100,000 charter members.” Quoting Lonnie Bunch, founding director, “there are few things as powerful and as important as a people, as a nation that is steeped in its history.”

Herman and I met Dr. Lonnie Bunch in Hilton Head, SC, a few months before the opening of the museum. He spoke to us about the plans and expectations. I had no idea of the magnitude and the quality of the museum, the exhibits and the planning that developed this wonderful experience.

Our tour was arranged by Dr. Rolando Herts, Director of The Delta Center for Culture and Learning and the Mississippi Delta National Heritage Area. An energetic and bright young man, Rolando took the picture of Herman and me at the South Carolina Rice exhibit. About half way through the tour, I recall telling him, “It’s hard to watch and relive your life as history.” There was so much to see and learn. It really takes more than a day to walk, sit and think about what you’ve seen or are seeing.

Obviously the developers, curators and archivists understood the impact of the museum. There were several spaces on each level . . . a room, a corner, a place to sit and quietly reflect on the experience. These spaces were absolutely needed. Sometimes one is overwhelmed by what happens as a video streams before your eyes. You are stunned by what you didn’t know; by what you knew but forgot; or by what you don’t want to remember. I used one of those spaces to cry . . . to just cry my heart out.

Herman and I were walking past the Woolworth Sit-in Stools, Interactive Lunch Counter exhibit. I asked a staff member about the Emmett Till Memorial. It was at the end of hall. I started walking and looked back at Herman. He indicated that it was going to be too much for him. I walked on alone.

There were two small rooms in the exhibit. A staff person stood in the outer room. It felt much like the vestibule of a church; but I wondered why the staff person was there. I would soon understand.

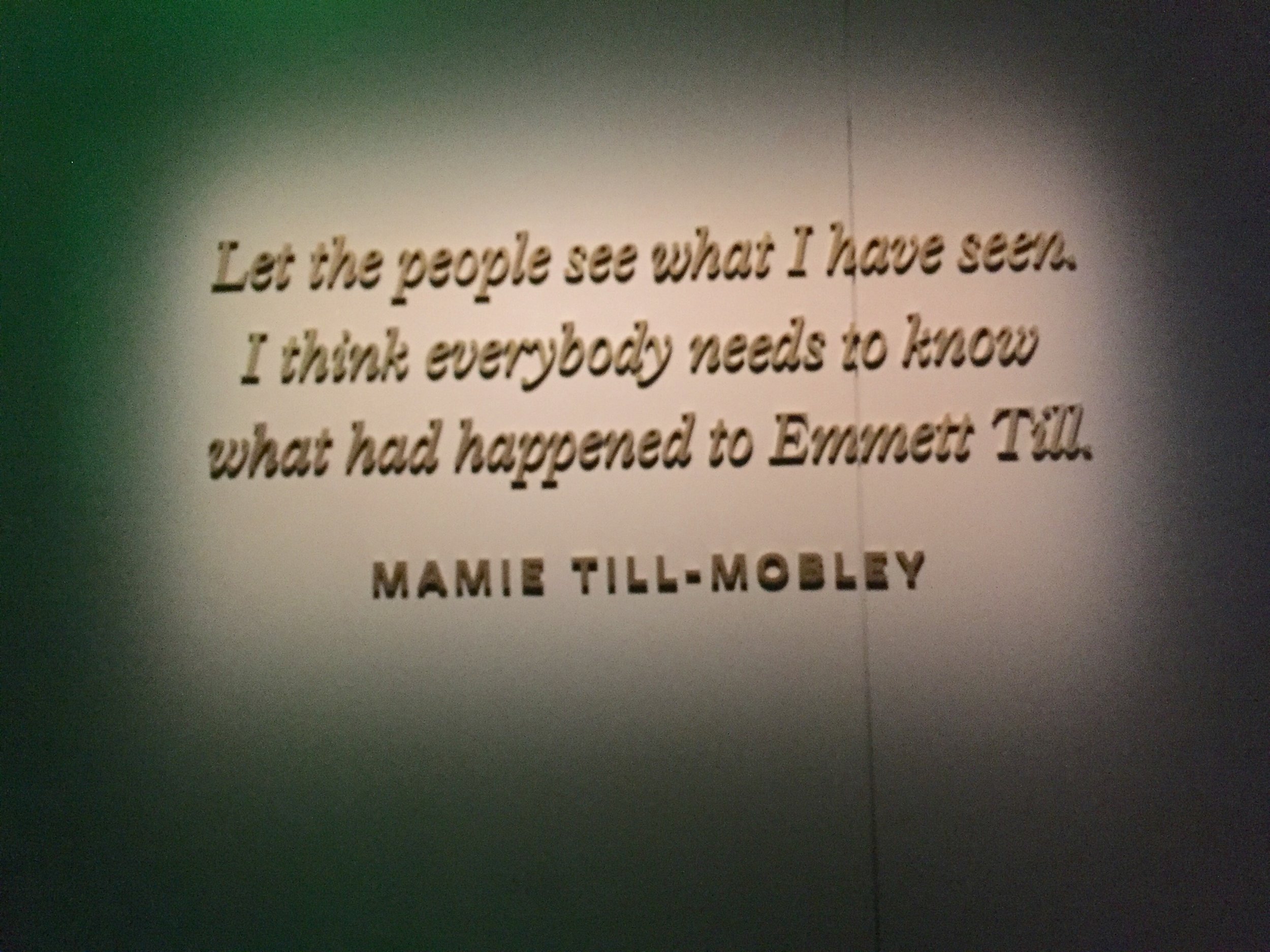

I looked at the artifacts and moved to the inner room. I found myself in a church service. Not just a Sunday service; but I had the feel of a funeral service. I sat down on the first pew and realized in front of me was the actual coffin that held Emmett Till’s body. I looked up and saw the procession and words of people speaking. I heard the choir singing, his mother speaking and the preacher preaching. There were photos of Emmett Till, the young teen, brutally killed in Mississippi and of his mother who insisted that the casket remain open, so the world could see what they did to her son.

I remembered Emmett Till’s story. He was from Chicago and went to visit relatives in Money, Mississippi, when he was killed. I was a child in Chicago when it happened. My mother showed me the article in Jet magazine. I believe my aunts attended the wake. Many of our neighbors, family and friends paid their respects also. I was afraid.

Sitting on the pew in the National Museum of African American History, I was transported to my childhood as I relived the past with an adult’s knowledge of the future. And, it hurt. It really hurt and I started to cry.

Rising from the seat, I found myself walking away from the exhibit. I looked straight ahead. I did not want to talk to anyone. Herman understood. I found my quiet place and I cried. There are rooms on every level of this museum where you can record your feelings and impressions. I used two of them as a way to unburden my long held memories and fears.

My God!

This was like no museum I had ever visited and that’s what makes it important and significant. There are many exhibits – joyful, inspirational, challenging, and interesting that make you smile and laugh. There are others that make you bow your head and cry. The museum elicits all of your emotions. Yet, there is a diversity of people around you who understand your feelings and share your experience.

It is a community. It is a museum. It is educational and, in ways, spiritual.

It is a must-visit of a lifetime.